How Nestlé Created Japan’s Coffee Culture By Targeting Kids

At 8 AM on a typical Tokyo morning in 2014, millions of Japanese workers clutched their coffee cups, a ritual so natural it seemed like it had always been part of Japanese culture. But this wasn’t always the case. In fact, this scene would have been unimaginable just a few decades earlier. This is the story of how Nestlé transformed Japan from a tea-drinking nation into the world’s fourth-largest coffee importer, using an unconventional approach that would reshape an entire culture’s relationship with a beverage.

In the 1970s, Nestlé faced what seemed like an insurmountable challenge in Japan. Despite pouring millions into advertising campaigns, promotional events, and price discounts, their coffee products gathered dust on store shelves. Japan remained steadfastly devoted to its centuries-old tea tradition. The company had tried everything in their traditional marketing playbook, but nothing seemed to work.

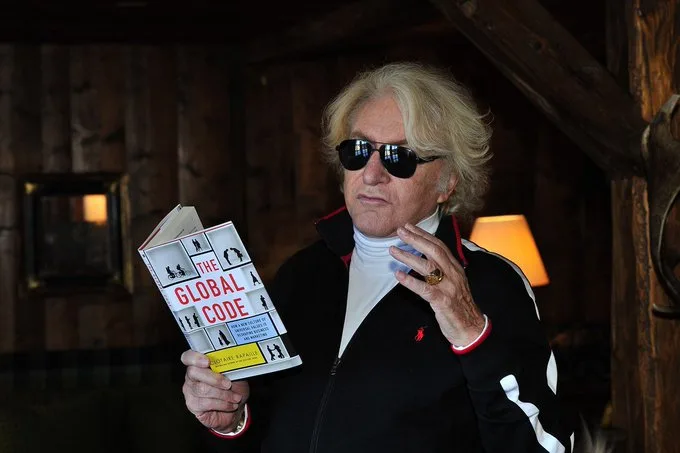

The situation forced Nestlé to confront an uncomfortable truth: they weren’t just selling a product; they were trying to introduce an entirely new cultural element into a society that had no emotional connection to it. That’s when they made an unusual decision that would change everything – they hired Clotaire Rapaille, a French child psychiatrist turned marketing expert.

Rapaille’s analysis revealed a fundamental insight that had eluded Nestlé’s marketing team: people form emotional bonds with foods they associate with childhood experiences. Japanese adults weren’t buying coffee because they had no nostalgic connection to it. The solution, Rapaille suggested, was counterintuitive – stop trying to sell coffee to adults altogether.

Instead of continuing their futile efforts to convert tea-drinking adults, Nestlé embarked on a long-term strategy that seemed radical at the time. They began creating coffee-flavored candy and desserts specifically targeted at children. Coffee-flavored chocolates, coffee jelly, and various sweets began appearing in stores across Japan. This wasn’t about immediate profit; it was about cultivating future coffee drinkers.

The strategy faced its share of skeptics. Some executives worried about the long-term investment with no guarantee of return. Others questioned whether children would even like the bitter taste of coffee-flavored treats. But Nestlé persisted, trusting in Rapaille’s psychological insight.

Then came the 1980s, and with it, the first signs that their unconventional strategy was working. The children who had grown up enjoying coffee-flavored treats were entering the workforce. Not only were they familiar with the taste of coffee, but they now had a practical need for its caffeine boost during long workdays. When Nestlé reintroduced instant coffee to this generation, the response was dramatically different from their parents’ rejection.

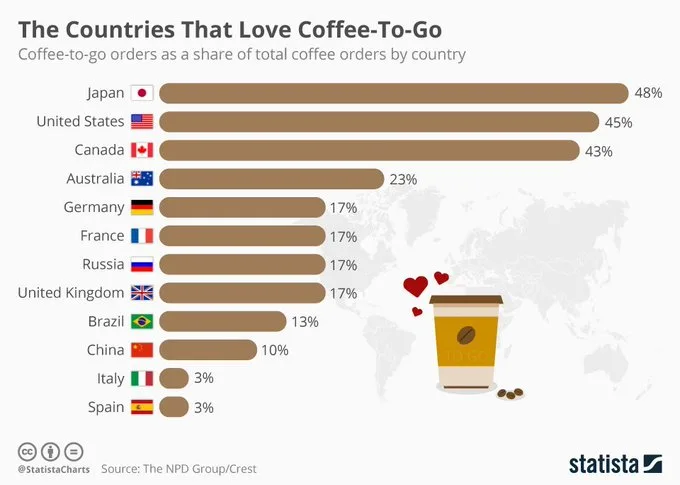

The success was unprecedented. Coffee consumption in Japan began to rise steadily, eventually reaching record highs by 2014. The country transformed into the world’s fourth-largest coffee importer, bringing in over 500,000 tons annually. Nestlé emerged as the undisputed market leader in Japan’s coffee industry, their patience and innovative strategy finally paying off.

This story illustrates a profound lesson about cultural change and market creation. Nestlé’s success came not from trying to force immediate change in adult behavior, but from playing the long game – creating cultural significance where none existed before. They understood that true cultural transformation happens not through aggressive marketing, but through carefully cultivated experiences and emotional connections.

Today, coffee is deeply woven into the fabric of Japanese society, from traditional kissaten coffee houses to modern vending machines on every corner. Few of the millions of Japanese coffee drinkers realize that their daily ritual began with a child psychiatrist’s insight and a company’s willingness to wait years for their strategy to bear fruit. It’s a testament to the power of understanding human psychology and the patience required for true cultural transformation.