Wild Japanese Macaques, Or Snow Monkeys, Uniquely Soak In Hot Springs To Reduce Cold-Climate Stress—A Cultural Habit Seen Only In This Jigokudani Troop

In the frosty heart of Nagano Prefecture, Japan, a curious and charming winter ritual has captured the imagination of travelers and scientists alike. Here, in the remote cliffs and forests of Jigokudani—aptly named “Hell Valley” for its volcanic steam and harsh terrain—wild Japanese macaques, also known as snow monkeys, have developed an extraordinary habit: they soak in hot springs.

Yes, you read that right. Monkeys. Taking hot spring baths.

A Chill, a Soak, and a Cultural Spark

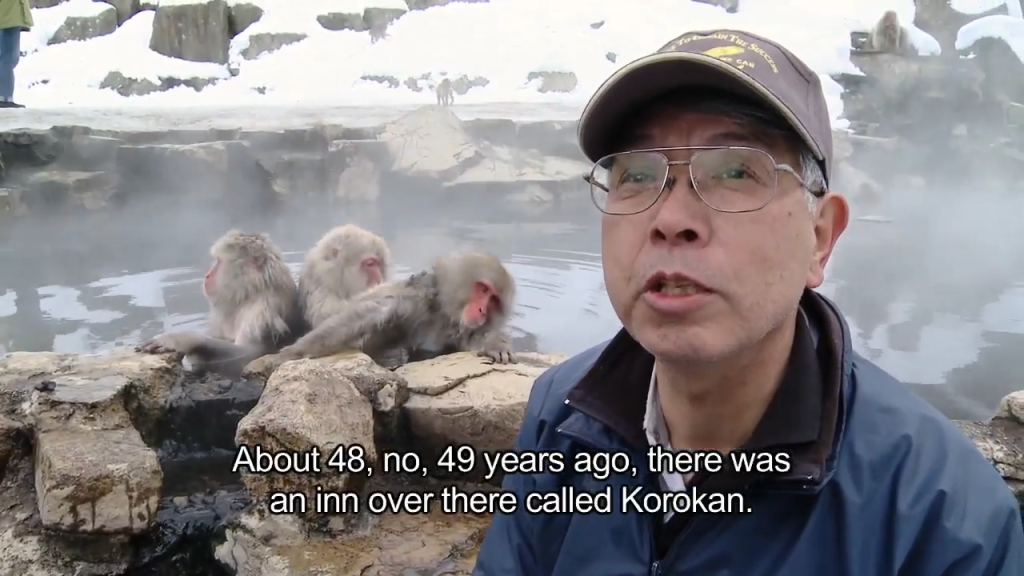

This behavior didn’t emerge from ancient monkey legends or mystical monkey monks. It began, rather unexpectedly, with one bold young female macaque in 1963. She was seen slipping into the steamy waters of an outdoor onsen (hot spring) near Korakukan, a traditional Japanese inn that still operates today.

Her fellow troop members watched. Then, one by one, they followed. Within a year, the phenomenon had drawn attention from researchers, and in 1964, Jigokudani Monkey Park was officially opened to provide the macaques with a dedicated hot spring—and to keep them from crowding around human guests in search of warmth and food.

But some locals trace the origins back even earlier. In the late 1950s, a local nature enthusiast named Sogo Hara began feeding wild monkeys to deter them from raiding farms. He offered treats like apples and soybeans near a hot spring. At some point, a curious monkey reached for an apple floating in the water… and may have decided the bath wasn’t half bad.

This quirky moment may have sparked a new cultural tradition—one now passed from generation to generation within a single troop.

Why Only Here?

This is where it gets fascinating. Japanese macaques live throughout much of Japan—including in other frigid, mountainous regions like those in Honshu and Shikoku. Many of these regions also have hot springs. Yet, only the troop at Jigokudani has adopted hot spring bathing as a regular winter practice.

Why?

Researchers believe this is a form of non-human cultural behavior—a practice learned socially rather than through instinct. Just like humans pass on family recipes or dances, the Jigokudani monkeys have passed on the art of soaking in onsen. And despite the chilly climate and nearby hot springs, macaques in other areas haven’t picked it up. The behavior remains completely unique.

A 2018 study by Kyoto University even confirmed that bathing reduces stress in these monkeys. Their cortisol levels—a marker for stress—drop after a nice long soak. Who can blame them? Hot water, cold snow, and zero responsibilities.

How to Witness the Spa Day

If you’re visiting Japan between December and March, this steamy monkey spectacle is one of the most magical winter sights you’ll find.

Planning a visit to Jigokudani? Here’s what to know:

- Location: Jigokudani Monkey Park, near the town of Yamanouchi in Nagano Prefecture.

- Best season: Winter months, especially after snowfall, when the monkeys’ steamy baths contrast beautifully with white surroundings.

- Access: A 1.6 km (1-mile) snowy trail leads from the park entrance to the hot spring. Wear sturdy boots!

- Rules: No feeding, touching, or bathing with the monkeys. (Yes, people have asked.)

More Than Just a Photo Op

Sure, it makes for one of the most Instagrammable moments in Japan. But look closer, and the snow monkeys of Jigokudani offer something deeper: a glimpse into how animal behavior can evolve through learning, observation, and perhaps a little curiosity and comfort.

In their steaming bath, these monkeys remind us that culture doesn’t belong solely to humans. Sometimes, it’s passed down by wet-furred bathers high in the snowy mountains—one splash at a time.